After reading Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction I found myself particularity thinking of the use and evolution of art as propaganda.

In his 1935 essay, Benjamin discusses the relationship between art and Fascism, stating the “logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life”. He further states “all efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war. This is a chilling statement, remembering that his essay was written in 1935 – four years before the onset of the Second World War. Before Hitler’s propaganda machine went into full swing, but not before Mussolini’s.

Shorthand typist at the centre of Hitler’s propaganda office, Brunhilde Pomsel said in an interview shortly before her death aged 106 “Those people nowadays who say they would have stood up against the Nazis – I believe they are sincere in meaning that, but believe me, most of them wouldn’t have.” After the rise of the Nazi party, “the whole country was as if under a kind of a spell,” she insists.

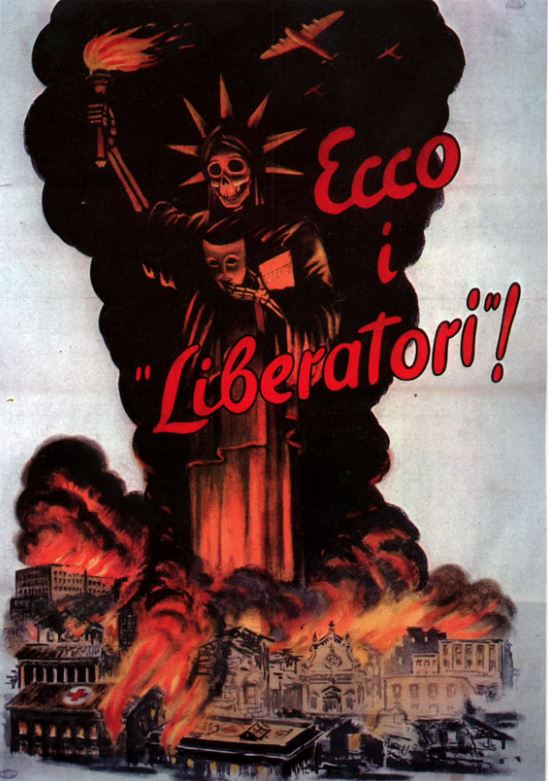

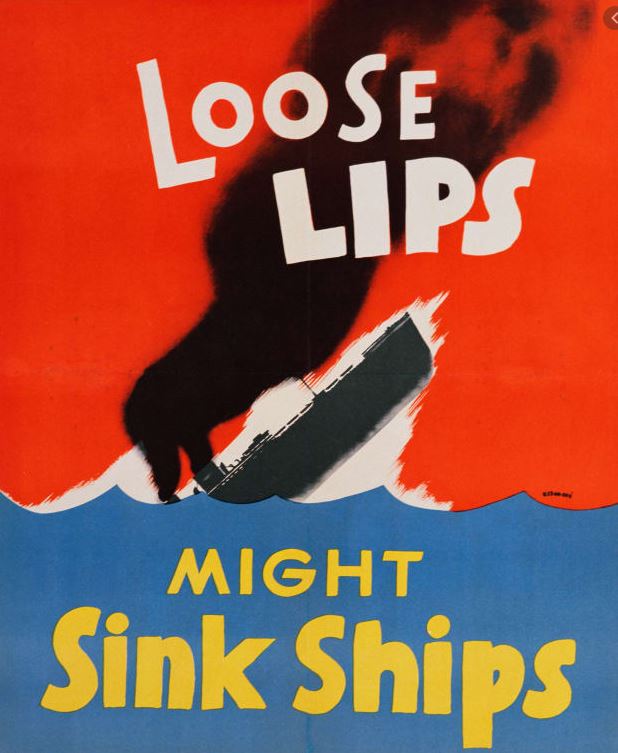

Hitler’s ally, Mussolini also took full use of images, films and photographs to tell a story. To package and market Italy as the new Roman Empire and Mussolini as the new Caesar. It’s important to point out, though, that the German and Italian regimes weren’t the only ones taking advantages of propaganda, The U.S. and U.K also had successful programs.

Further chilling too, as I continued to read Benjamin’s essay, I was reminded of a story I had heard once about the leader of North Korea’s propaganda machine and the kidnapping of an actress and her director husband from South Korea.

Described as a socialist state and a totalitarian dictatorship, North Korea has been ruled by the Worker’s Party of Korea since 1948. North Korea’s Supreme Leader today is Kim Jong un and the position of Supreme Leader has been hereditary since his Grandfather, Kim Il Sung lead the country out of Japanese occupation in 1945.

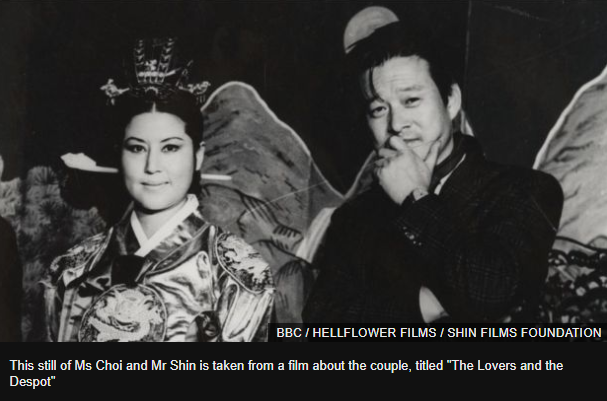

In 1978, Kim Il sung’s son, Kim Jong-il had been so successful as the head of North Korea’s Propaganda and Agitation Department that he had helped his father to achieve almost god-like status. Films, posters and an unprecedented statue building schedule had helped him, but something was missing. An avid cinema fan, by the 1970s he was director of the Motion Picture and Arts division of the PAD and directing films himself, but Kim Jong-il believed he could go further, ingratiate himself into his father’s graces even more. He could continue to build his father’s status by putting North Korean cinema on the map – by abducting South Korea’s most famous and successful film making team. Actress Choi Eun-hee and her director husband Shin Song-ok. So, in 1978, he did just that. Taking the couple from their lives in South Korea – and their children – Kim Jong-il demanded the couple make films in his father’s favour.

From 1978 – 1986 Choi and Shin made 7 films to make Kim Jong-il happy (to make his father proud and to show him he could be a worthy leader upon his death), to make South Korea jealous and to gain international attention. They did just that and while attending a film festival in Vienna, they escaped in 1986.

The North Korean incident occurred in the 1980s, some fifty years after his writing and I wondered what Benjamin would have made of it. What would he have made of the advances in technology? Would he have been surprised or not? Would he have felt more positive about the further modernisation of art and its various applications? Digital photography and the transition of photographs and films from their negative and print forms to digital data which can then be manipulated. Almost any kind of art work can now be produced or reproduced digitally, even an original painting with the right software. Somehow I struggle to think he would. Sadly, as he passed in 1940, we’ll never know, but I think he definitely could have added the North Korean example as an exclamation point to his essay.

References:

Benjamin, W. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Illuminations. Editor Hannah Arendt. Schocken Books, 1969

Connolly, Kate. Joseph Goebbels’ 105-year-old secretary: ’No one believes me now, but I knew nothing’. The Guardian. 16 August, 2016. Online. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/15/brunhilde-pomsel-nazi-joseph-goebbels-propaganda-machine

Holt, Nick, Clifton, Dan and Finney, Ben. Inside North Korea’s Dynasty. 2018.

Leave a comment